This week I will publish several guest posts on NikonRumors. If you have an interesting Nikon related topic you want to share, contact me. You can see all previous NR guest posts here. The first article is about the time-lapse video “Astronomer’s Paradise” by Christoph Malin (images by Christoph Malin and Babak Tafreshi). Here is the video (click on images for larger view):

“Astronomer’s Paradise“ is the first episode of a three parts Atacama Desert Starry Nights time-lapse series, starting with footage on the ESO* (European South Observatory’s “Cerro Paranal” site). The series will be included as a bonus on the ESO’s 50 years anniversary DVD/Blue Ray disc expected to be released this summer. This time-lapse movie was made from DLSR still images from the November 2011 TWAN imaging expedition to Paranal assigned by the European Southern Observatory.

The first week of shooting took place at ESO’s famous Cerro Paranal site. The second week, we travelled to the ALMA OSF facility, near San Pedro de Atacama, where we were scheduled for imaging sessions at the 5000m high Chajnantor Plateau, the site of the ALMA radio telescope array.

In total Babak Tafreshi** and me*** photographed 14 nights in a row from usually 05:30 p.m. to 08:00 a.m. This was demanding, especially the second week at 5000 m. But even during our two days off, we continued photographing the stunning Chilean night skies on several locations, as they had been steady and clear all week.

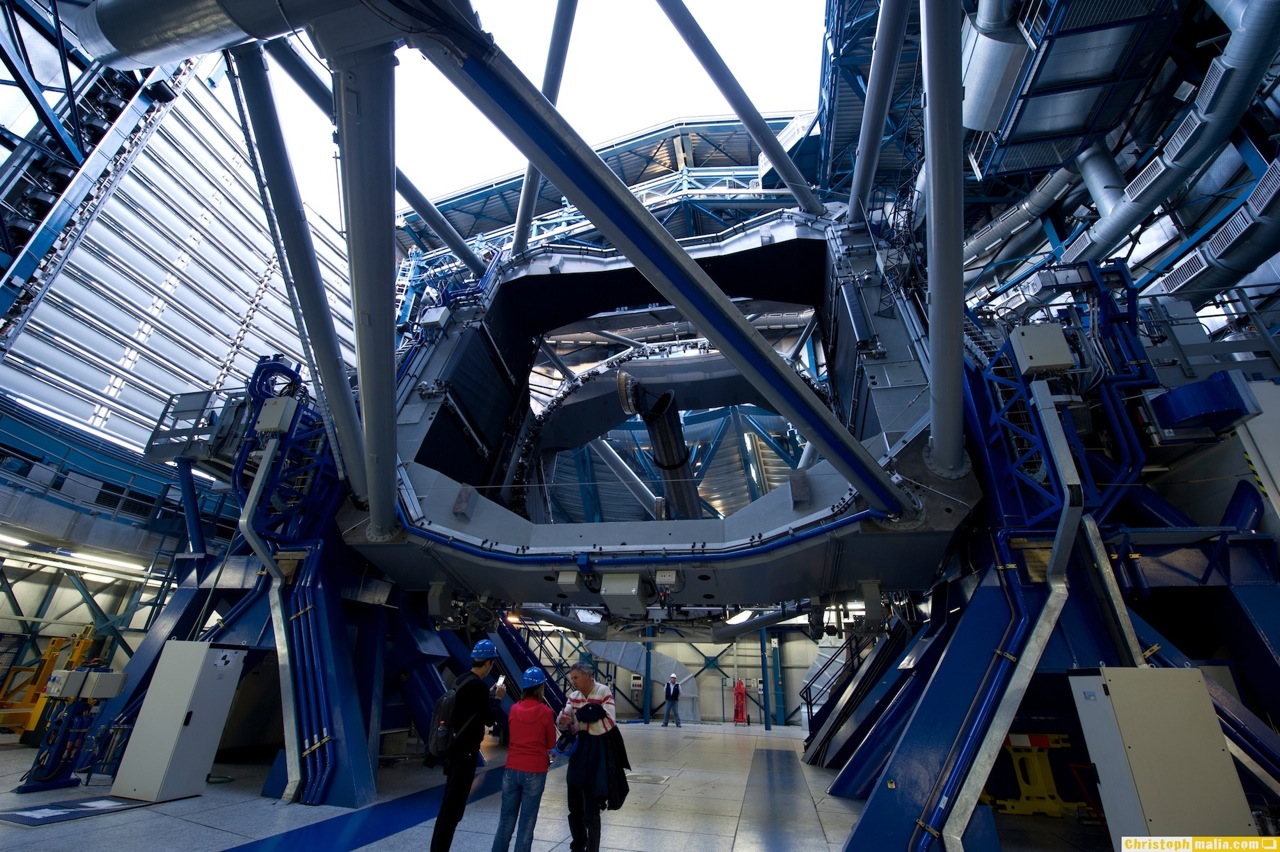

Cerro Paranal is an astronomers paradise with its stunningly dark, steady and transparent sky. Located in the barren Atacama Desert of Chile, it is the home to some of the world’s leading telescopes. Operated by the European Southern Observatory, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) is located on the Paranal mountain, composed of four 8.2 m telescopes which can combine their light to make a giant telescope by interferometry.

Four smaller auxiliary telescopes, each 1.8 m in aperture, are important elements of the VLT interferometer. Paranal was selected by ESO for cutting edge astronomical observations also because of the sky transparency and steady atmospheric condition, which let astronomers peer into tiny details in the deep cosmos.

Babak Tafreshi: “It is an amazing experience to be under an ideal night sky, a pure natural beauty unspoiled by urban lights. On Cerro Paranal in the Atacama Desert you look all around the horizon and there is no prominent sign of city lights, neither direct lights or light domes. There are not many locations left on this planet where you can still experience a dark sky like this. I have been to similar dark skies in other continents from the heart of Sahara in Algeria to Himalayas or islands in the Pacific. But what makes Atacama beat others is being dry and clear for so many nights per year.”

Walking on the desert near Paranal between the scattered stones and boulders on the pale red dust felt like being on Mars. The clear Chilean night sky with its zillions of stars was so bright that you could see the shadow of your own feet on the ground. Yet the Atacama desert surroundings are unforgiving and zero fault tolerant. Working in the dark was even more challenging. Safety precautions are omnipresent at Paranal and ALMA, and the places are – except the ambient light of the Milky way that over time sets to below the horizon – very dark at night. Cars must drive with parking lights at low speed. If you get lost or have an accident at the driest place on earth without water or rescue, you will die within days because of rapid dehydration.

Some words on how the video was produced:

On Location

We usually started transporting and building up equipment from 05:00 p.m. on at the Paranal Platform. While Tafreshi is known for a lightweight two-camera setup that makes him flexible, I am the time-lapse guy that usually juggles with 3 to 4 cameras, external power sources of all kinds, a dolly and two astronomic heads with their controllers. Moving around the equipment during location changes, changing batteries where necessary, adjusting the controllers etc. kept me mostly busy during the night, although one usually tries to get at least one or two hours nap in between. This helps on staying concentrated for the tasks. Sometimes, when all equipment was running well, we could just hold breath for a moment and enjoy the beautiful skies above Paranal.

After sunrise we disassembled and packed everything back in, which usually took time until 08:00 a.m., then we went down from the mountain to our rooms to recharge batteries, setup image transfers and finally get some sleep until about 12:00. Then we had breakfast with other astronomers (we worked like them in astronomer’s shifts). After that we usually went back to our rooms and started processing the footage from the night before until we moved up the mountain for the next night session. Kind of a tight schedule, but on a place like Paranal, where scientific operations are planned 365 days down to the minute, the clock ticks and the output has to be the best possible.

On equipment

I used the following cameras with their built in intervalometers and lenses:

- 2 Nikon D3s

- 1 Nikon D700

- 1 Nikon D7000

- 2 AFS 12-24/2.8, AFS 24-70/2.8, AF 16/2.8 Fisheye, AF DX 10/2.8 Fisheye

Dolly and astronomic heads:

- Dynamic Perception Stage Zero Dolly with MX2

- Merlin with MX2 and Astrotrac TT320-XAG

The D3s and D700 were my proven workhorses. The D7000 serves me a lightweight backup, I normally use it for hiking and some HD filming, but also as a time-lapse machine. I like to shoot the D7000 with the fisheye lens. Both D700 and D7000 were used with the MB- D10 and MB-D11 battery grips. Where possible, we used the camera’s external AC adapters.

ISO

To my experience the D700 works best up to ISO 2500, with up to ISO 6400 possible for “emergency cases”. The D3s is in it’s own league. It doesn’t matter much if you work ISO 2500 or 6400 with the D3s and ISO 8000 to 10000 are also not much of a problem. Grain on D3s is beautiful and not visible on time-lapse videos, same goes for the D700. The D7000 has different ISO performance due to the DX chip with high density – I usually used it up to ISO 1600 range, above that things get noticeably grainy. This grain is not a problem on stills, but when it gets “moving” on time-lapse it doesn’t look good.

Batteries

When doing time-lapse with sometimes over 3600 images per night per camera, batteries become a problem and it gets worse with low temperatures and freezing desert winds, especially with the D3s. Regardless if new or used batteries, with long exposures the D3s burns amps and doesn’t last longer than 3 hours. The problem is that once you change the D3s battery, the interval is interrupted and the sequence finished. So unless you have an AC adapter power source, you cannot go trough the night with the D3s.

The D700 usually lasts 3-4 hours (if you use MB-D10 with EN-EL4a). Changing the battery is not a problem on the D700 because you always leave the EN-EL3e in the body. Hopefully Nikon will think about an external battery source for the D4 in the future. The D7000 is excellent on battery life: one EN-EL15 usually lasts 5-6 hours, double that with MD-D11 battery grip.

Storage

For in-camera storage I use 32 to 64 GB Transcend, Sandisk and Express CF and SD cards as well as FireWire CF card reader for my MacBook Pro. During the whole trip I shot about 520 GB of data, stored on a Raid 1 FW800 disk (NEF and JPG files). Finally, about 35000 time-lapse images were processed on my side, Tafreshi had about the same amount (in between he also did some time-lapses). Altogether we selected 7500 frames for this part of “Astronomers Paradise”.

Transporting equipment to Chile

All went well until an Air France employee in Munich checked my LiIon batteries one hour before departure. What followed was bizarre – nobody knew if I can get on the plane with those batteries. Several departments between Paris and Munich got involved and at the end the flight captain decided that I can fly with my original Nikon LiIon batteries in my luggage. He was just as astonished as I was. Incredible.

On processing the time-lapse sequences and the video

I do all transitions, deflickering and other image processing prior to rendering with Apple Aperture (see this videos). The video was edited and rendered with Final Cut Pro 10, motion and compressor were used for all the time-lapse sequence RAW rendering. Final Cut 10 has improved a lot with their latest 10.0.3 update and is fast and fun to work with – much faster compared to Adobe After Effects. No more delays on working with RAW files, no more conversion to JPG or downsizing necessary (like with AE). Motion is ultra fast on rendering NEFs, about 4-5 times faster then AE, it is impressive.

Martin Kornmesser, ESO and Hubble Telescope Imaging Artist also helped on processing and gave some of my footage the distinct dark punchy ESO look.

I hope we captured the magic of this very special place – this is how the night sky looks like without light pollution. We need more people to be aware of light pollution. Waste of light is waste of energy and money and harms the nature and us.

Our next ESO/TWAN time-lapse movie will be released in March and will focus on the northern Atacama, the Valley of the Moon, and the other major ESO observatory – the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA).

If you like, check an article on my time-lapse photography in the current winter issue of Nikon Pro (page 16) or in the Nikon Pro iPad issue.

With best regards,

Christoph Malin

*ESO – the European South Observatory – is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organization in Europe and the world’s most productive astronomical observatory. From its headquarters in Garching, Munich it operates three sites in Chile — La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. It builds ALMA, the worlds largest radio telescope array at the 5000m high Chajnantor plateau together with other international partners and designed the European Extremely Large Telescope.

**Babak Tafreshi, 32, is an international astrophotography legend (special project coordinator of the UNESCO International Year of Astronomy 2009, Lennart Nilson Prizeholder 2009 and founder of TWAN – the World at Night, an international awarded night sky world heritage photography project).

*** Christoph Malin, 42, is ESO photo ambassador and an Austrian based outdoor journalist and astrophotographer specializing in time-lapse night sky photography of the Alps and other mountain and desert regions.

See also those related National Geographic posts:

- New time-lapse gives rare glimpse at Atacama’s starry nights

- New mountain time-lapse: A [Sound] Garden of Night Lights

- New astro time-lapse video: “The Island” showcases astronomy haven

Previous guest posts by Christoph Malin:

You can follow Christoph’s work on his website, Facebook and Twitter.