My X-Pro1 sure looks pretty impressive all decked out with Nikon’s 80-400mm zoom mounted on it via the Metabones Speed Booster adapter.

In today’s guest post Tom Grill will review the Metabones Speed Booster Nikon G lens to Fuji X-mount camera adapter ($429). More information can be found on Tom’s blog (click on images for larger view or follow the links for the full resolution samples).

We are so accustomed to thinking of Nikon as a camera company that it is easy to forget the company began in 1917 primarily as an optical firm and continued that way for quite awhile. Nikon lenses for all uses, both scientific and photographic, were legendary, and remain so even today. It is with good reason film makers like putting Nikon lenses on their cine cameras, and Nikon lenses are carried into outer space. The quality of Nikon lenses was noticed by photo-journalists covering the Korean War,. These photographers began adapting the Nikon lenses to fit their 35mm cameras. Even Canon used Nikon optics on its first cameras. With the advent of mirrorless cameras making it easy to adapt DSLR optics, adapters are rapidly becoming available for mounting Nikon Optics on most of these cameras. Primarily, these adapters are straight through with no optical elements. They simply form a bridge between the lens and camera. More sophisticated models can also pass data from the lens to the camera. Because the newer Nikon G lenses do not have external diaphragms some lens adapters now come with aperture control built into them.

Then along came the Metabones Speed Booster.

There are any number of adapters on the market for mounting a DSLR lens to a mirrorless camera, but the limitation has always been that in doing so the practical focal length of the lens is altered. On an APS-C size sensor, like that in the Fuji X cameras, the lens focal length is multiplied by a factor of 1.5x, meaning that a 50mm full frame lens converts to a 75mm focal length on the smaller X sensor.

The Speed Booster is an intriguingly novel product that allowed the mounted lens to maintain its actual focal length when mounted on a camera with a sensor that is smaller than full frame. Even better, as a byproduct of the conversion, the maximum lens aperture of the lens increases by one full stop so that the maximum aperture of a f/2.8 lens, for instance, would become f/2 when using the adapter. Sounds like a photographer’s holy grail — one that definitely peaked my interest enough to give it a try.

To accomplish this miracle of conversion, the adapter must introduce an optical element within the lens to camera path, and therein lies a cause for concern. Any time an optical element — no matter how well it is designed and manufactured — is inserted between a lens and the camera some degradation of the image will usually take place. It might be slight, but it will be present. The best scenario would be when a camera manufacturer designs a specific device for one of its own lenses, as would be the case of Nikon designing a tele-converter to take into consideration the specific design of its own lenses and cameras. But even here, the rule follows that the insertion of any external optical elements into the path of lens-to-camera will compromise the optical quality of the original lens design to some degree. In the case of the Metabones Speed Booster the question becomes: Can it perform its miracle of conversion with a minimum amount of interference to the original design of the lens so the end product remains within acceptable limits. Let’s have a look.

The Speed Booster does have aperture control for the Nikon G lenses, such as the 50mm f/1.4G lens mounted on it above.

When I first began this hands on testing series I was mounting the Speed Booster on common focal length Nikon lenses, but it quickly became apparent that this was not very practical. After all, why use a Nikon lens interpreted through an auxiliary optical device, when a similar focal length Fuji lens of exceptional optical quality already existed. And so I realized that the Speed Booster would be most practical if it could convert lens types that were not available to the Fuji X-series APS-sized sensor. Throughout these tests I used the Metabones converter on all types of Nikon lenses, but paid particular attention to those focal lengths and lens types that were not otherwise available in a Fuji X-mount, such as the Nikon 80-400mm zoom, the Defocus Nikkors, tilt-shift models, and, yes, even the Nikon 16mm fisheye.

The Speed Booster shown here mounted on a Defocus Nikkor 105mm lens with a Nikon 16mm fisheye nearby.

The device is called the “Speed Booster” because a byproduct of its reducing the image size to fit onto the smaller APS-C sensor of the Fuji X cameras is that the amount of light is also increased proportionately so that the maximum aperture of the lens is increased by one full stop. For instance, a lens with an f/2 maximum aperture, would become the equivalent of an f/1.4 lens when mounted on the Speed Booster. That is a nice plus.

The Speed Booster does not transfer any of the Nikon lens data to the Fuji camera. Consequently, auto-focus on a Fuji X camera is not possible. The latest Fuji firmware update did improve the manual focusing system on the X-Pro1, and I found it to be quite helpful in acquiring a sharp focus.

The Metabones Speed Booster is 1 1/4″ deep, and weighs in at a hefty 7.4oz (210g). The aperture on Nikon G lenses is controlled by turning the numbered ring shown in the two photos above.

You be the judge. I performed many tests with a wide variety of some of the best Nikon lenses, and included plenty of downloadable high res versions of my test images below. Take a look at them and judge the technical results of the Speed Booster for yourself.

I did stick to the better quality Nikon lenses for my test, figuring that if the Speed Booster wouldn’t work well with these, it certainly wouldn’t perform well with consumer lenses. In general I found that performance with primes was better than with zooms, and better with long zooms than short zooms. This is to be expected. Short zoom lenses are very complex optical systems. Introducing another lens element into the light path is asking for trouble.

The two sample images below were taken using prime lenses, the Nikon 50mm f/1.4G lens for the top photo and 35mm f/2 lens for the bottom image. Both show good resolution when used with the Speed Booster.

Click here to download a high res version of this file.

Click here to download a high res version of this file.

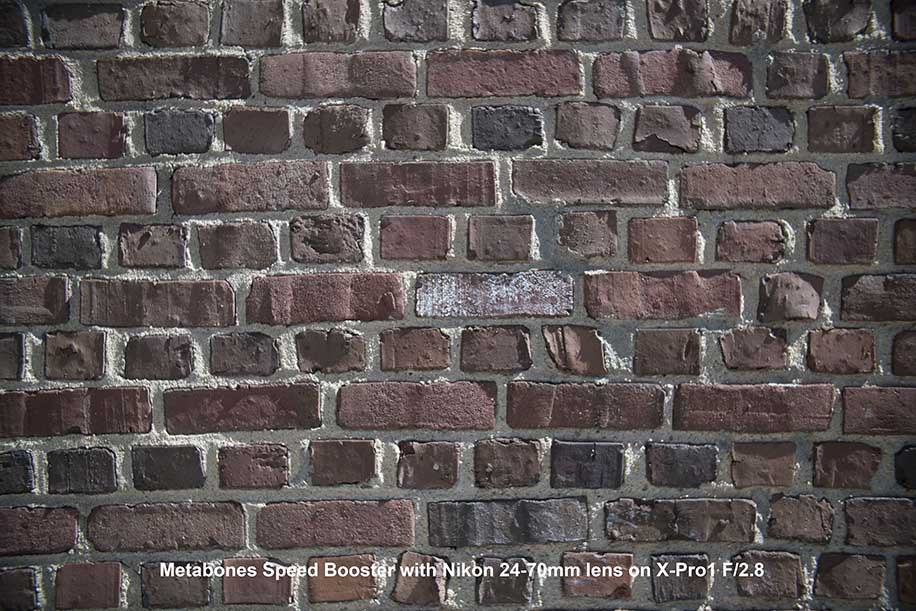

One lens I tested was the Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom. This is one of Nikon’s better zooms. The results are shown in the two photos below. Here you can see that at the longer focal length the results are acceptable, but when pulled back to 24mm the results were very poor, showing extensive vignetting and fringing.

Click here to download a high res version of this 70mm file.

The image above and below were both taken with the Speed Booster and Nikon 24-70mm zoom. For the photo above the lens was racked out to 70mm. For the bottom photo the lens was set to 24mm. Note that at the shorter focal length there is considerable vignetting and also some corner fringing.

Click here to download a high res version of this 24mm file.

I did a brick wall test with the 24-70mm zoom set to a mid range. You can download the test images below and judge for yourself. The center of the images was sharp at all apertures, but I continued the tests down to f/11 and still had considerable corner softness and color fringing.

This resolution test was done with the Nikon 24-70mm zoom on the Speed Booster. You can download the various aperture test images below.

Use the links below to download the high res samples of aperture tests of the brick wall test. You will notice that even stopped down to f/11 there is still considerable softness and fringing in the corners.

- Click here to download f/2.8 high res sample.

- Click here to download f/4 high res sample.

- Click here to download f/5.6 high res sample.

- Click here to download f/8 high res sample.

- Click here to download f/11 high res sample.

The portrait test below was done with the Nikon 70-200mm f/4 lens mounted on the X-Pro1. It is shot against a very strong late day setting sun producing low contrast and considerable flare — a tough situation for any lens. The resulting image is acceptable but lacking in contrast. When I shot the same portrait later with the lens mounted straight onto a Nikon camera, the resolution and contrast were much sharper.

Click here to download the high res version of this file.

For the series of tests below, the Speed Booster was mounted on Nikon’s new 80-400mm zoom set to different focal lengths and distances. In general, all of them are just a tad softer than I would expect from this lens when it is used alone. Because this was a test, I didn’t do anything to improve the sharpness. I do think all of these images would actually produce quite acceptable results with some very minor post-processing work. Fringing in any of the images was easy to deal with when bringing the RAW image in with Adobe Bridge, and resolution could have been improved with the addition of increased clarity, also in Adobe Bridge.

Click here to download the high res version of this file.

Click here to download the high res version of this file.

Click here to download the high res version of this file.

Conclusion:

The Metabones Speed Booster is a new concept of lens adaptability in the digital age, and one that is exciting for those of us who would like to extend the range of systems like the Fuji X cameras to take advantage of some of the better, and rarer optics already found on full frame cameras. The system is not perfect. On the Fuji it is manual focus only. Thankfully, Fuji improved its focus peaking and extended it with the latest firmware update. At least manual focusing is now easier and more accurate.

As already mentioned, optical quality will be degraded somewhat simply by inserting another optical element in the image path. Nonetheless, the center sharpness with almost all lenses I tested remained very high. It is only in the corners that things began to fall apart, as the image softened, vignetting increased, and color fringing crept in — all of which was more apparent with zoom lenses than with primes, and most of which was easily corrected in post-processing.

This is an expensive item. A Fuji version costs $429. I suppose the price can be justified if you factor in the savings gained by adding a whole new arsenal of other lenses to the Fuji system. The Metabones Speed Booster means that over night my Fuji X-Pro1 becomes a more practical professional system with the addition of lenses such as my tilt-shift Nikkor. Of course why I would want to use such a lens on the X-Pro1 instead of on a Nikon full frame is whole other issue. I am not sure where a product like this will lead us. It is certainly intriguing, and begins to open new possibilities as the new mirrorless camera systems become more popular.

This photo was taken using a Nikon 24-120mm zoom mounted on the X-Pro1. Note the corner fringing in the high res sample. Click here to download a high res version of this file.

If you have an interesting idea for a guest post, you can contact me here.